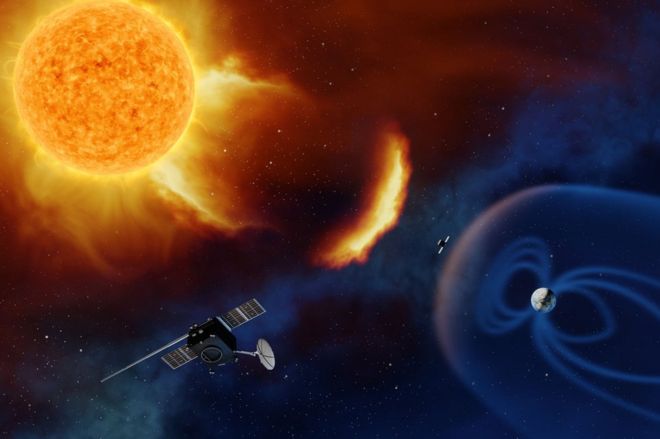

Image copyrightESA

Image copyrightESAUK scientists and engineers will play a leading role in developing a satellite that can warn if Earth is about to be hit by damaging solar storms.

The European Space Agency has requested studies be undertaken to design the mission that would launch in the 2020s.

Explosive eruptions from the Sun can lead to widespread disruption on our planet – degrading communications, even knocking over power grids.

The satellite’s observations would increase the time available to prepare.

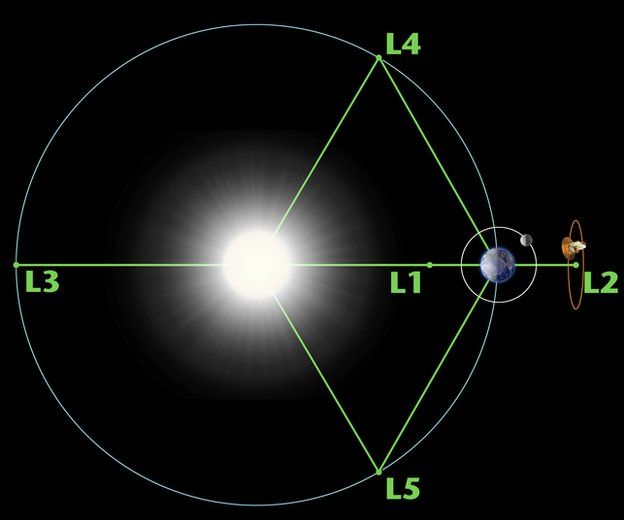

Esa has a working name for the new mission – “Lagrange”, which reflects the position the satellite would take up in space.

The plan is to go to a gravitational “sweetspot” just behind the Earth in its orbit around the Sun known as “Lagrangian Point 5”.

Spacecraft that are sited there do not have to use so much fuel to maintain station – but there is an even bigger operational rationale to use this location: it is the perfect spot to see that part of the Sun which is about to rotate into view of the Earth.

“So, not only do you get a preview of the active regions and how complicated they are, but if the Sun throws something out you also get to track it from the side,” explained British solar physicist Prof Richard Harrison.

“Imagine a fist coming directly at your face – it’s difficult to say how far away it is; but if you see that fist from the side, it’s much easier,” he told BBC News.

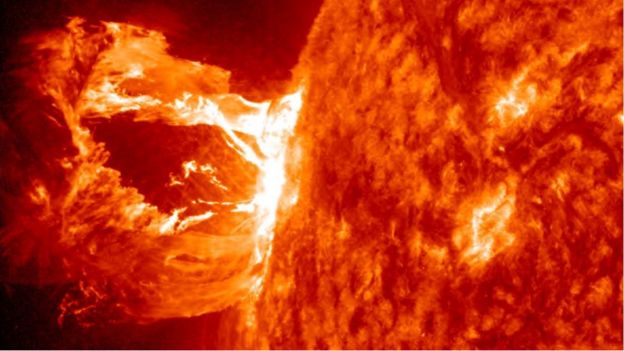

Image copyrightNAS/SDO

Image copyrightNAS/SDOEsa signed four so-called Phase AB1 contracts on Friday at its mission control centre in Darmstadt, Germany.

These include two parallel industrial studies – to be led by Airbus UK and OHB System of Germany – to spec the spacecraft bus, or chassis, and the process for integrating all the satellite’s instruments.

The aerospace companies will also work out how the entire mission would be managed, from launch to the end of service life.

The actual design of the onboard instruments is the subject of the other two contracts. Both of these will be directed by British-led consortia.

RAL (Rutherford Appleton Laboratory) Space will assess the requirements of the mission’s “remote sensing package” – that is, the instruments that discern what the Sun is doing by looking at it.

The UK’s Mullard Space Science Laboratory (MSSL) will scope the “in-situ package” – those instruments that investigate the Sun’s activity by directly sensing emitted particles and magnetic fields.

Although led from Britain, these efforts will of course draw on talents from across European member states.

The different Lagrangian Points

Image copyrightESA

Image copyrightESA- These are the sweetspots in the Sun-Earth-Moon system

- They are places where gravitational forces balance out

- Satellites at these locations use less fuel to maintain station

- L5 is at a 60-degree offset, and follows Earth in its orbit

- A complementary US mission would very likely go to L1

Solar storms are a common occurrence. Our star will sometimes despatch big bursts of shortwave and longwave radiation, superfast particles and colossal volumes of charged gas (plasma) in our direction. This material is also threaded with strong magnetic fields.

When these emissions encounter Earth, they can kick-off a number of effects in modern infrastructure, from glitching electronics in aircraft avionics and in orbiting spacecraft to increasing the interference heard on radio broadcasts, such as those from the BBC.

Numerous studies have warned of the possible consequences of a major solar storm impacting Earth.

Just last year, a government report said the UK economy would lose £1bn for every day the GPS satellite-navigation service was unavailable.

“What we need is a ‘solar sentinel’, watching the Sun to tell us what is going to happen in advance,” said Dr Ralph Cordey from Airbus UK.

“This is an area where the UK’s expertise is well established. It’s also the case that the impacts of ‘space weather’ are regarded as a priority in the UK with the issue recognised in the register of civil hazards, along with pandemic flu, severe flooding and volcanic eruptions.”

The Lagrange mission concept is being overseen by the Space Situational Awareness programme at Esa to which the UK committed €22m, over 4 years, at the last gathering of Europe’s space ministers in December 2016.

When the ministers next meet, in December 2019, they will have the results of the new studies and should hopefully be in a position then to sanction the mission’s full development.

Image copyrightNASA/ESA/SOHO

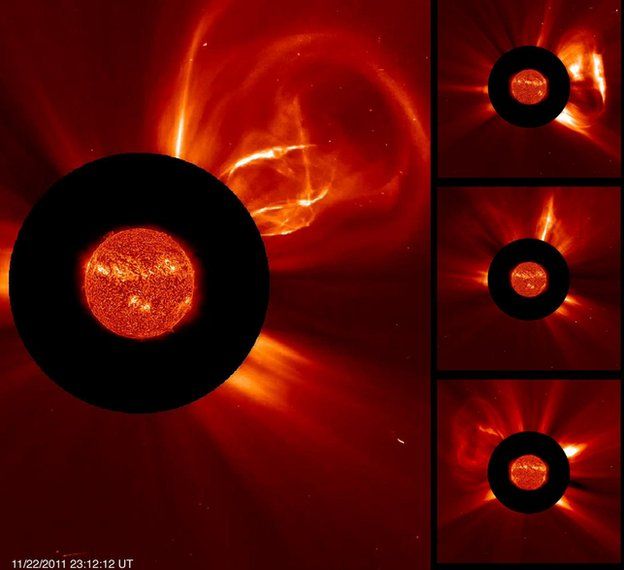

Image copyrightNASA/ESA/SOHOOne key instrument that will have to be carried is a coronagraph.

This is a device that blocks the full glare of the Sun’s disc so that the beginnings of an eruption are more easily seen.

At the moment, space weather forecasters are relying on a coronagraph on a 20-year-old spacecraft called Soho.

“A coronagraph gives us the first warning that something really is happening,” said Prof Harrison, who is the chief scientist at RAL Space.

“A coronal mass ejection is a million times weaker in intensity than the Sun itself. It’s a contrast problem: if you didn’t block off the Sun, you wouldn’t see it.”

It is likely the Americans will launch a similar mission in the coming years that will sit directly in front of Earth in line with the Sun. Taking the two perspectives together will give solar storm forecasters the best assessment of potential impacts.

Source : BBC

Weblifedata News and Magazine

Weblifedata News and Magazine