Two schoolchildren died on Tuesday and 14 others suffered bullet wounds when a classmate opened fire outside a school in Benton, Kentucky. It was the third US school shooting in 48 hours and the 11th in the three weeks since the start of the year.

The victims were Bailey Holt and Preston Cope, both 15. A 15-year-old boy was arrested and charged with the attack.

The story fell somewhere into the middle of the day’s news agenda. “Americans have accepted these common atrocities as part of life here,” wrote one commenter on the New York Times website. “Another day, another shooting spree, and no political will to do anything about it.”

But there is political will building behind a certain sort of gun legislation — reforms that aim to increase, rather than decrease, the number of firearms in schools and other public buildings, and arm teachers and school staff as a means of defence.

Hours after the shooting in Kentucky, Republican State Senator Steve West rushed to file a bill that would allow Kentucky schools to have armed school marshals patrol the site. His bill joins another in the state which seeks to loosen gun restrictions around college campuses.

Mr West’s bill received cross-party support from state Democratic Senator Ray Jones. “We need armed officers in every school in Kentucky,” Mr Jones said. “That is a small price to pay if it saves one child’s life.”

The bill joins a raft of state legislation in recent years designed at putting more guns in schools. Most recently, the Michigan State Senate passed a bill in November which would allow teachers at primary, middle and high schools to carry a concealed handgun in class. Similar bills have been filed this year in Florida, Indiana, Pennsylvania, Mississippi, South Carolina and West Virginia.

If successful, those states would join at least nine that already allow some form of concealed carry in high schools. Each fatal school shooting reignites a long-running debate over whether the solution is more gun control, or more guns.

“If we want to talk about preventing school shootings, we should be talking about stopping kids getting their hands on guns in the first place,” said Adam Skaggs, chief counsel at the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. “Those are the laws we should be looking at.”

Good guys, bad guys

Efforts to arm teachers and school staff were jumpstarted in the wake of the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook elementary in Connecticut, in which 20 children and six teachers died. Facing a public outcry at the massacre, and renewed calls for gun control, the NRA pushed heavily in the opposite direction.

“The only way to stop a bad guy with a gun is with a good guy with a gun,” said the NRA’s Executive Vice President Wayne LaPierre a week after the shooting, and the catchphrase morphed into a key legislative priority for the NRA.

The lobby group published a report calling for armed officers or staff in every school in America, and in 2013, the year after Sandy Hook, seven states enacted laws permitting teachers or school staff to carry guns.

Image copyrightFASTER

Image copyrightFASTER“Over the past two or three years we’ve seen an explosion of legislative proposals to force schools to permit guns or to arm teachers,” said Mr Skaggs. “And it’s not just pushing the idea that people need guns in schools to be safe, it’s the idea that people need guns everywhere – city streets, public parks, even government buildings.”

But advocates say these kinds of reforms are the only meaningful way to protect schoolchildren. They point in particular to more rural schools, where an emergency response from police may take too long in the context of an active shooter incident. They also argue that gun-free zones are creating “soft targets”.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESIn Kentucky, home to Tuesday’s shooting, Republican Tim Moore has introduced bills in 2017 and 2018 in an effort to reduce restrictions around guns on school and college campuses.

“Whenever in our country people with evil intent seek to harm others, including innocent children, they will seek locations where they know there’s going to be minimal chance of resistance,” he said in a telephone interview.

“Allowing law abiding citizens who are properly trained, properly vetted, with a thorough background check and criminal check … that is a deterrent.”

‘Mindset development’

School shootings erupted into the public consciousness in April 1999, when Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold murdered 12 students and one teacher at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado. That massacre has since been eclipsed by shootings at Virginia Tech college (33 dead), Sandy Hook elementary school (25 dead), and 203 other shooting incidents in or around schools.

According to an FBI study of 160 active shooter incidents between 2000 and 2013, nearly a quarter occurred in educational settings, and more of half of those were at junior or secondary schools.

Fourteen years after Columbine, and eight miles down the road, Littleton suffered another shooting. Karl Pierson, 18, went to Arapahoe High School in December 2013 with two guns and shot 17-year-old Clare Davis in the head, before killing himself in the school’s library.

One of the first police officers on the scene that day was Swat team member Quinn Cunningham. Still a serving officer, he now trains teachers to carry firearms and respond to active shooter situations.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

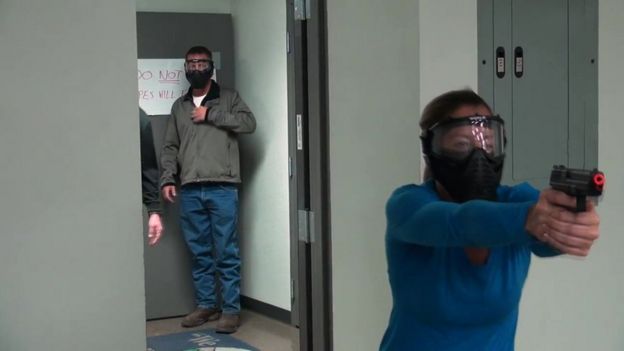

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESThe three-day “Faster” training courses – funded by the Ohio-based Buckeye Firearms Foundation – include a day of “mindset development” – which involves preparing teachers for the possibility that they will have to shoot dead one of their own students.

Mr Cunningham, 44, asks the teachers to close their eyes and imagine the student entering the classroom with a gun. In reality, a teacher might have just a split-second to assess the situation and respond. This is the most difficult and emotional part of the training, and reduces some of the participants to tears.

“But if we can have them win in their minds first, against that student, then when it comes to the actual incident they will prevail,” Mr Cunningham said.

Five members of staff from Fleming High School in north-east Colorado volunteered last year for the training, which takes place in the summer break to keep students in the dark about who’s involved. One teacher who took part, who asked to remain anonymous, said she decided to picture her favourite student during the preparation exercises, in an effort to harden herself to the worst possible eventuality.

“Teachers aren’t really supposed to have favourites but you know, you have the ones that are close to you,” she said. “But if that student made the poor decision to endanger everyone, I’m going to have to do something about it.”

The school now has posters at every entrance stating that some of its teachers are armed. The students spent “about a week or two” trying to work out who was carrying guns, before giving up, the teacher said. Her wardrobe changed “quite a bit” to accommodate a handgun, she said.

The volunteers at Fleming High were subjected to background checks and a voice stress analysis, similar to a lie detector test, said school superintendent Steve McCracken. All five passed and now carry guns in the school.

“At the end of the day, no one in our school or community is in favour of having guns, but if a bad guy comes to the school we are now able to take care of it,” he said.

Image copyrightFASTER

Image copyrightFASTER“We do not have a local police department in our little town, and the sheriff’s office could be at least 15 to 20 minutes away on a good day. The main reason for this is to close that gap.”

Some staff vocally opposed the presence of guns and one teacher later left the school, but the general reaction from staff and the community was supportive, he said.

In a 2013 poll by the National Education Association, only 22% of teachers said they approved of the idea of arming staff, while 68% of teachers said they were opposed.

‘Playing Rambo’

In Michigan, when the state senate passed legislation in November that extended concealed carry to high schools, churches, day care centres, and sporting events, former teacher-turned-Democratic state senator Jim Ananich was among a vocal minority who opposed the bill. He said he thought the “overwhelming majority” of his former colleagues would be against the idea.

“Trying to play Rambo just doesn’t fit with the reality of what happens in a stressful situation,” he said. “Untrained individuals are much more likely to shoot a bystander, a police officer, or a child.”

The three days of training administered by Faster – and the legal minimum standard in Michigan of just eight hours for armed teachers – was not nearly enough, he said.

“Pursuing the NRA philosophy that you can put guns into the hands of teachers and untrained individuals, and expect them to make decisions that law enforcement or military are supposed to make, is backwards and it’s dangerous.”

Image copyrightFASTER

Image copyrightFASTERThose fighting to keep guns out of schools say arming teachers is a bad solution to the wrong problem, particularly in states that lack laws around securing firearms in the home.

According to the Giffords Law Centre, 27 states and the District of Columbia have some sort of Child Access Prevention (CAP) laws, which dictate how securely guns should be stored in the home.

The CAP laws in Kentucky, where the shooter reportedly took a gun from his parents’ closet, are among the weakest of all those states. Parents or guardians will only break the law if they knowingly provide a gun to a child convicted of a violent crime or likely to commit a crime.

On the ground, groups like the Campaign to Keep Guns Off Campus are fighting state-by-state against the NRA, its state-level affiliates and other gun-advocacy groups to defeat pro-gun schools legislation.

“We – the collective gun violence prevention community – are defeating most of the bills right now, but the intensity on the other side is there,” said Andy Pelosi, director of Keep Guns off Campus. “The NRA has its fingerprints all over this issue now, they want to push guns everywhere,” he said. The lobby group did not respond to a request for comment.

Weblifedata News and Magazine

Weblifedata News and Magazine